Giving voice to genius: Helping Hawking speak

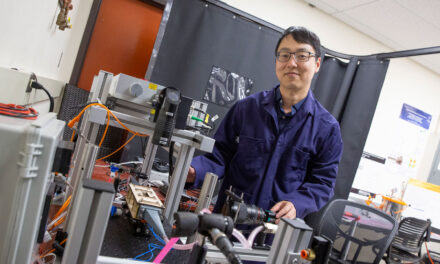

Famous physicist Stephen Hawking (foreground), disabled by neuromuscular disease, depended on scientists and engineers who developed the technologies that enabled him to overcome the loss of speech. Speech synthesis and acoustics experts who helped him included (from left behind Hawking) Arizona State University alum Michael Deisher and his colleagues, the late Edward Brucket and Corine Bickley, pictured here in 2005. Photograph courtesy of Michael Deisher.

Stephen Hawking’s contributions to theoretical physics are considered no less than revolutionary in advancing our understanding of the workings of the universe.

Along with that career accomplishment, Hawking, who died in March at age 76, was also a best-selling writer and public speaker who contributed to fostering a broader public fascination with science around the world.

That he was able to do so despite decades of physical debilitation resulting from the neuromuscular disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was made possible by other scientists, engineers and technicians.

One of those engineers is Michael Deisher, who earned a master’s degree and a doctoral degree in electrical engineering from Arizona State University in the mid-1990s.

Deisher began a full-time job with the Intel Corporation just days after completing his doctoral studies and research. He’s been with the company — working in a facility near Portland, Oregon — for 22 years, playing roles in many technological advances and enhancements that have earned U.S. patents.

Among them is what he describes as “the experience of a career,” collaborating with fellow experts in his field, and with Hawking, to improve systems that enabled Hawking to communicate.

Deisher led an Intel-sponsored team that developed speech synthesizer software as part of the computer system Hawking used to communicate.

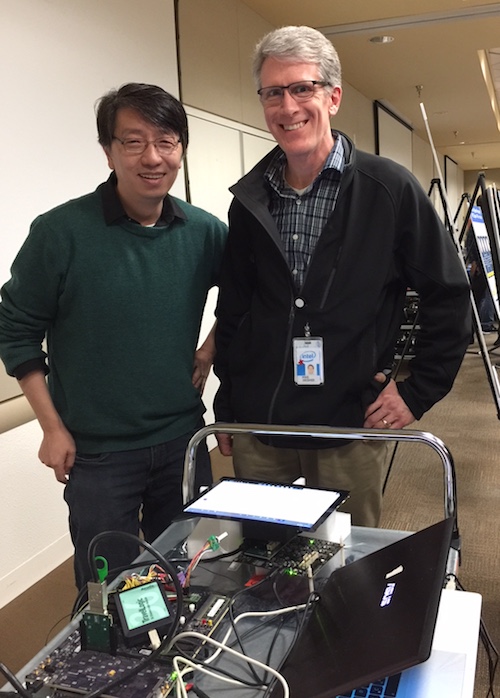

Intel engineers Kevin Zhu (left) and Michael Deisher pictured at a recent Intel internal computer architecture summit. Deisher has worked at Intel since earning his doctoral degree in electrical engineering from Arizona State University in 1996. Photographer: Gayle McCarthy/Intel

The project “was really interesting to me as an engineer because it shows how temporary measures using the best tech we have available at any one time can lead to unintended consequences later on when better tech is developed,” Deisher says.

“When Hawking lost his voice, he adopted the best technical solution at the time. Then he became world famous and that solution [his voice] became part of his persona. Then the company that made the technology went out of business,” he explains.

Speech synthesis technology then fundamentally changed to produce more human-like voices, causing a shortage of researchers and technologies that could produce the voice Hawking wanted.

“But computer hardware, like human ‘hardware,’ does not have an unlimited life expectancy,” Deisher says. “Hawking’s body was expected to wear out before his hardware, but it looked like the computer hardware would fail before his body would. He was faced with the prospect of losing a part of his identity, his voice, for a second time.”

Intel had already provided the custom laptop attached to Hawking’s wheelchair. Intel executives then sought help from speech technologists to create software that perfectly emulated Hawking’s hardware-generated voice from the original 1988 discontinued circuit board.

Deisher’s team produced a system that gave Hawking a voice through a “flight notebook,” allowing him to communicate during air travel or whenever he was not in his chair equipped with other communications devices.

“Our software was installed on Hawking’s flight notebook,” Deisher says. “He continued to use the hardware voice when in his chair, and right before his death one of the original developers of the hardware voice unearthed the original software code and was able to achieve an exact match to the hardware voice for the flight notebook.”

Through this assistive text entry system, Hawking could select letters or words from a display. His eyeglasses were equipped with an infrared sensor that detected movement he made with his cheek to stop a cursor on the computer monitor screen.

When he finished a sentence, Hawking was able to send it to speech synthesizer hardware under his chair that would essentially read aloud in his iconic voice what he had written.

ASU research helps overcome technological challenges

The experience that prepared Deisher for his work with Hawking began with the research in speech signal processing he conducted during his doctoral studies at ASU.

His efforts in that area were part of an ASU-Intel partnership to pursue advances in architectures for mobile communications systems.

“We were trying to solve problems for devices like cell phones or anything you could speak through,” Deisher explains.

His focus was on enabling those devices to clearly transmit voices while minimizing or eliminating extraneous noise. Deisher would test his algorithms by enlisting friends to stand on the roadside along traffic-heavy University Drive near campus and talk into voice recorders while vehicles sped past.

Deisher incorporated a statistical model of the throat, mouth and vocal chords into a speech estimation algorithm by integrating novel pitch tracking and vocal tract models to remove the traffic noise from the voice recording.

Deisher’s improvements to the recording devices, and other achievements in speech enhancement and noise reduction technologies and programs, led to his dissertation research paper, which was published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

Other papers based on that work — co-authored by his doctoral studies advisor, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering Professor Andreas Spanias — were featured in several major science and engineering conference publications.

The project he collaborated on with Hawking in 2005 and 2006 proved to be as challenging as any he had encountered during his graduate school years or since. The speech synthesizer hardware was aging and there was an urgent need to replace it with software before it failed completely. But not just any software voice would do.

The famous scientist did not want to sound more natural or have a generic “human” voice. “He wanted to sound exactly like the hardware voice that had become part of his public persona,” Deisher says.

Attempting to reproduce that voice required a painstaking process that melded the unique characteristics of both old and new technologies into the program Deisher’s team developed.

Despite the difficulties, “it was still very exciting,” Deisher says. “It was great to be able to use what I know now, and some of the knowledge I gained studying at ASU, to help him sound more like ‘himself’ than he would have otherwise been able to at that time. That was really gratifying.”

Path from ASU to rewarding career

Deisher, who grew up in rural Illinois, earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Valparaiso University in Indiana, which he attended with the aid of academic and football scholarships. He played on the team for four years. In his senior year he was a first-string offensive guard.

He was further aided in college and on his career path by the dean of Valparaiso’s engineering school at the time. The dean had a colleague at a Goodyear Aerospace facility west of Phoenix and got Deisher an internship there.

Deisher spent two summers and three semesters during his undergraduate years in that internship in Arizona. Duirng that time, he took a class at the ASU West campus and learned about research ASU engineering faculty were doing in areas that interested him.

“The timing was good for me at ASU,” he recalls. “They had rebooted the signal processing program. They had new funding and had hired new faculty. There were really a lot of new ideas floating around and everyone was working hard to make an impact.”

Along with studies and research that he says “gave me a lot of practical experiences that have been valuable for working in industry,” Deisher also met the fellow electrical engineering graduate student, Gim Mui Lim, who is now his wife.

The couple came back to Arizona last year to celebrate their 20th wedding anniversary. The trip included visiting ASU’s Tempe campus and posing for a picture in front of the Engineering Research Center, where they once did research together.

“Returning to ASU brought back some great memories,” Deisher says, “and reminded me how much the people, classes and research projects at ASU contributed to the skills I rely on as a principal engineer at Intel.”